Archdiocese's list shows it kept secret seven priests credibly accused of sexually abusing children

By Madeleine Baran, Minnesota Public Radio

-

Listen The List: Hear more on this report

Dec. 5, 2013

Explore the full investigation Clergy abuse, cover-up and crisis in the Twin Cities Catholic church

The Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis acknowledged Thursday that it had kept secret for decades the names of at least seven Catholic priests it considers credibly accused of sexually abusing children.

Archbishop John Nienstedt revealed the names on a list of 34 priests posted to an archdiocese website. The names are from a list the archdiocese created in 2009 of priests accused of child sexual abuse. However, Nienstedt now says four of the priests should not have been included.

• Breaking news: Archdiocese names 30 priests linked to child sexual abuse over six decades

Three-fourths of the priests on the list are already known to the public through lawsuits and media reports. The 34 priests served in nearly half of the archdiocese's parishes.

"These disclosures being made now, and the changes in our disclosure practices generally, are part of a comprehensive and cohesive set of actions we have been taking here in the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis this fall to address the issues associated with clergy sexual misconduct," Nienstedt said in a statement.

The disclosure came three days after an unexpected ruling by Ramsey County Judge John Van de North in a case filed by a victim of clergy sexual abuse. Van de North ordered the archdiocese to release the names of 33 priests included on a 2009 list, as well as the names of other priests accused since then.

• Related: Judge orders names of 46 accused priests to be released

Van de North's ruling is likely the first time a judge in the U.S. has forced the release of a list of "credibly accused" priests, according to clergy abuse researchers and victims' attorneys.

The public naming of the seven priests kept hidden by the archdiocese now raises the possibility of police investigations and further lawsuits.

It also calls into question the archdiocese's previous statements. Church officials have long argued that the public didn't need to see the names because most of the priests were either dead, falsely accused or already well known.

• MPR News investigation: Archdiocese under scrutiny

"I don't know what good would be served to their family and survivors and stuff if they've already been exposed and vilified and humiliated," then-archdiocese spokesman Dennis McGrath told MPR News in 2005. "Now that they're dead, let the dead lie. Not all of them are dead, I'm sure they've gone elsewhere. But it doesn't make much sense in our mind to do that again. We care more about the victims. Priests have already been dealt with."

However, only 11 of the priests are dead. Seven of the priests on today's list were not known to the public as abusers. And in court on Monday, an archdiocese attorney didn't say any of the men had been falsely accused. Rather, he said that three of the priests have been accused of abuse that could not be substantiated by church investigators.

Nienstedt said the seven previously unnamed priests "who have had credible accusations and substantiated claims against them of sexually abusing a minor in our archdiocese" are: Timothy McCarthy, Paul Palmitessa, Alfred Longley, Joseph Pinkosh, Richard Skluzacek, Raymond Walter and Robert Zasacki.

Two of the men — Pinkosh and McCarthy — live in the Twin Cities. One lives in California; the rest are dead.

None could be immediately reached for comment.

Nienstedt vowed greater transparency on Thursday. "Now, if the claim is credible and can be substantiated, our new disclosure practices will require that claim to be disclosed on our website," he said.

He declined to be interviewed.

Victims' voices

Victims of clergy sexual abuse said the release of the list will help protect children from priests whose abuse was hidden for so long that they can no longer be prosecuted.

Jim Keenan, who was sexually abused as a child by the Rev. Thomas Adamson, said the disclosure will also expose how bishops protected priests at the expense of children.

• Related: Alleged sex abuse victim goes public with complaints (November 2010)

"It's so critical because it pops a hole in their balloon that they have the right to hide and harbor pedophiles," said Keenan, 46. "It says to the world this is what they were doing."

Keenan has fought hard for the list's release. Rather than accept a financial settlement from the archdiocese, he demanded the names be made public. When the archdiocese refused, he walked away with nothing and was later sued by the archdiocese for its legal costs.

"There's not enough money in the world they could have given me to keep that list silent," he said. "Because if a victim came up to me in three to five years or 10 years or 15 years and said, 'I was abused by one of the priests on the list but I'm glad you got your settlement,' I could not have dealt with that."

The big picture

The national clergy sexual abuse crisis of more than a decade ago left the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis mostly unscathed. Armed with policies and promises, church leaders convinced parishioners that the big scandals found in Boston, Chicago and Los Angeles would never happen here.

Victims who tried to sue the archdiocese often failed. A state law said child sexual abuse claims needed to be filed before the victims reached age 24. Most don't come forward until years later.

Victims' attorney Jeff Anderson responded by turning his attention to the list and relentlessly pushed for the names to be made public.

He praised the judge's decision Monday. "What the survivors want most, and what we want most, is the kids to be protected ... and today we made a stride in that direction," he said.

Nienstedt, who vowed last month to begin releasing the names, faces a widening clergy sexual abuse crisis that threatens his leadership of the archdiocese's 800,000 parishioners and more than 400 priests. It began in September when an investigative report by MPR News revealed top church officials had failed to warn parishioners of sexual misconduct by a priest who was later convicted of abusing two children.

Subsequent reports by MPR News showed the archdiocese protected a priest who admitted to sexually abusing boys on an Indian reservation in the 1970s, gave special payments to pedophiles and failed to turn over possible child pornography to police.

• Related: Abusive priest hid in plain sight for years, retired quietly to New Prague

Many of the revelations came from Jennifer Haselberger, a former top church official who resigned in protest of the archdiocese's handling of clergy sexual abuse cases in April.

The reports shook the archdiocese and led to the resignation of Nienstedt's top deputy, the Rev. Peter Laird. As the scandal worsened, Nienstedt was forced to postpone a $160 million capital campaign. At the same time, a new state law allowed victims of child sexual abuse a three-year window to file older claims. Hundreds of victims are expected to file suit, attorneys predict, and the archdiocese has begun planning for bankruptcy.

The list

The battle over the list began in 2004, when the archdiocese told researchers at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice that it knew of 33 priests accused of sexually abusing children. It did not provide the names.

Researchers used the information from dioceses around the country as part of a study on the prevalence and causes of clergy sexual abuse, funded by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops.

In 2009, attorney Anderson asked a judge to order the archdiocese to provide the names and personnel files of the 33 priests as part of a lawsuit brought by Keenan, the man abused as a child by Adamson.

Ramsey County Judge Gregg Johnson ordered the archdiocese to provide the information under seal. It remained under seal after the case was thrown out.

The list released today includes the 33 names from the sealed list. However, Nienstedt separated four of the names from the others and provided a brief explanation for each:

— One priest had no allegations of child sexual abuse against him on file.

— Another had no record of any claims of child sexual abuse in the archdiocese.

— Another priest had been credibly accused of sexual misconduct with a "young woman" in the early 1970s but a private investigator "has not determined whether a claim of sexual abuse of a minor was or can be substantiated."

— The fourth priest was accused of child sexual abuse, but a private investigator hired by the archdiocese reported finding "no credible, corroborating or supporting information which would validate [the] claim of sexual abuse."

The list includes one additional name — the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer, who was arrested and convicted of child sexual abuse after the list of 33 was created.

The Diocese of Winona has also been ordered to release its list of 13 accused priests by Dec. 17. Both dioceses will have until Jan. 6 to release the names of priests accused since the lists were created.

The list published on the archdiocese's website Thursday includes each priest's years of birth and ordination, as well as a parish assignment history, current status and city of residence. For the deceased priests, it also states the year of death.

It includes many familiar names, such as the Rev. Robert Kapoun, an accordion-playing priest known as the "Polka Padre" who resigned in 1996 when an alleged victim took him to court.

The list also names two priests who were criminally convicted for child sexual abuse: the Rev. Gilbert Gustafson and the Rev. Michael Stevens. Most of the other priests have never been investigated by police.

Seven unknown abusers

Nienstedt has declined to explain why he didn't report the allegations against the seven previously unknown priests to police. Archbishop Harry Flynn, who led the archdiocese from 1995 to 2008, also declined interview requests.

The archdiocese provided little detail on the seven names.

The list clearly shows, however, that bishops protected the identities of several priests long after they died. The Rev. Alfred Longley, who was identified publicly as an alleged abuser for the first time today, died in 1974.

Child sexual abuse: Get help

Others on the list, including the Rev. Robert Zasacki, who died in 2008, and the Rev. Richard Skluzacek, who died in 2012, narrowly escaped public scrutiny in their lifetimes.

Skluzacek served in seven parishes from 1957 to 1990 — including two parishes, Most Holy Redeemer in Montgomery and St. Nicholas in New Market, that employed another alleged abuser, the Rev. Clarence Vavra. Skluzacek was accused of fondling a 16-year-old boy in 1975 and agreed to follow unspecified restrictions, according to a document reviewed by MPR News.

Skluzacek's final assignment was as a chaplain at the Minneapolis V.A. Medical Center from 1990 to 1998. He was "permanently removed from ministry" in 2005 and died on Feb. 25, 2012.

The remaining priests whose allegations were not previously known are between ages 62 and 82.

McCarthy lives in St. Paul. At age 67, he is among the younger priests on the list.

Palmitessa, 82, lives in Santee, Calif. He served at parishes in Maplewood and Zumbrota and continued to engage in ministry outside of Minnesota until last year.

Pinkosh, 70, left the ministry in 1992 after serving in four parishes in 20 years - St. Joseph in Hopkins, St. Wenceslaus in New Prague, Holy Cross in Minneapolis and St. Patrick in Shieldsville. He lives in Columbia Heights.

• MPR News investigation: Archdiocese under scrutiny

New questions emerge

The lack of reporting to police has raised questions of fairness for both priests and their alleged victims.

The release of the list does not address concerns that the archdiocese hasn't properly handled reports of abuse. The list includes only priests with allegations that the archdiocese has classified as substantiated or who were included on an older list. An archdiocese spokesman won't say how church officials decided which charges were substantiated.

An MPR News investigation has found that top church officials often relied on informal meetings or private investigators to determine a priest's guilt or innocence. If an allegation was deemed credible, church leaders would transfer the priest to another parish or, in more recent years, remove the priest from ministry. The archdiocese rarely followed official Catholic Church procedures, known as canon law, for handling abuse allegations.

• MPR News investigation: Archdiocese under scrutiny

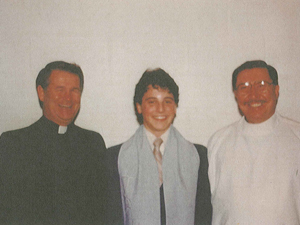

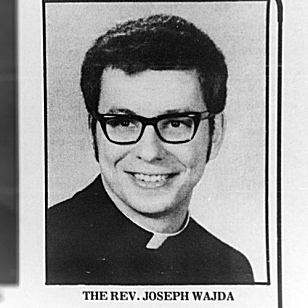

Joseph Wajda, one of the men on the list, said the archdiocese failed to follow canon law in his case. Several men have accused Wajda of sexually abusing them as minors, and the archdiocese has provided financial settlements in every case. And yet Wajda, 66, denies the allegations and has appealed to the Vatican for relief.

"Once you're accused, you're guilty, you know, until you prove your innocence," he said. "That's not the American way, that's not even what's supposed to be happening with the canonical norms."

Lists lead to more questions

Public pressure and legal settlements have forced about 30 dioceses around the country to release their own lists in the past decade.

Full investigation coverage

Help us tell this story

Contact the reporter

No two lists are the same. Some dioceses include photos and descriptions of the abuse and how the church responded. Others, like the list released today, provide no information about most of the allegations.

The Archdiocese of Boston publishes detailed information on priests who sexually abused children. It also publishes the names of deceased priests who were accused but never investigated and the names of priests currently under investigation.

In other dioceses, the lists are more haphazard.

The bishop of Monterey, Calif., disclosed the names of seven accused priests in a letter to parishioners in 2004. The diocese of Peoria, Ill., released a statement in 2002 that included the names of seven accused priests.

The bishop of Bangor, Maine, disclosed the names of nine abusive priests at a news conference in January 2007 and told reporters, "I have become increasingly concerned about the possible risk of re-offense in the cases of those who have not been publicly identified." However, the diocese has not posted the names on its website.

In 2004, the Archdiocese of Milwaukee released the names of 43 priests with substantiated allegations of child sexual abuse. In April of this year, it posted thousands of pages of internal documents on its website after it became clear that a judge would order them released as part of bankruptcy proceedings. The archdiocese's website also includes each priest's assignment history, a brief narrative of the abuse and how church officials responded. Some of the profiles include photos of the priests.

Lists often prompt more questions and controversy, said Terry McKiernan, founder of a nonprofit website called Bishop Accountability that tracks abusive priests.

"Immediately, people are going to want to know what those allegations were, how many there were, what parishes the abuse allegedly took place in," McKiernan said. "I think we're going to find that although there's a sigh of relief that we have the lists, or at least a portion of the lists, immediately there are going to be additional questions."

McDonough, the priest who faced criticism in recent weeks for his handling of clergy sexual abuse cases as the top deputy for Archbishops John Roach and Harry Flynn from 1991 to 2008, anticipated that same concern in an interview with MPR News last year.

Releasing lists will only make people wonder about the quality of the archdiocese's records and whether all names have been disclosed, he said.

"The list-making and publication that's happened in some places has not resolved the trustworthiness questions," he said.

McDonough added there was no need to release a list because loyal parishioners know the archdiocese has handled abuse allegations responsibly.

"If it becomes an issue of trust with people, whom we don't think are just running a marketing campaign, I think you'd see us change in a heartbeat," he said.

Sasha Aslanian, Mike Cronin, Meg Martin, Tom Scheck and Laura Yuen contributed to this report.